- By Rachelle Fox : article, web design and photographs.

- By Tamara Jabi : video*, infographics and production.

- *Ça Marche video and interviews by Rachelle Fox, Audrey Folliot and Leah Batstone.

Chapter 1: The Beginning

At the height of the AIDS crisis in the late 80s and early 90s, being diagnosed with HIV meant preparing for death. That was the standard medical advice from doctors trying to manage a disease they didn't understand. Opportunistic infections ravaged bodies. Effective treatments didn't exist. A patient's chances of survival were bleak. HIV/AIDS turned life into a ticking clock, counting down the years, months and days that remained.

In the media, words such as "plague" appeared, fuelling a panic that blazed through communities, inciting fear and intolerance. If you were ill, you were often abandoned and left to face the darkest moments of your life alone. People didn't want to be "contaminated." So ignorance, rejection and death became the status quo.

To cope with this harsh reality, some people living with HIV turned to drugs and alcohol, existing in a state of numb intoxication to avoid the pain. Others chose to volunteer with HIV/AIDS organizations, finding a certain peace in the act of helping those who could no longer help themselves. Hope was in short supply. Even if you weren't actively sick the idea that you might survive was rarely entertained.

Of course, people did survive. Michael survived.

Today, he works for AIDS Community Care Montreal. An organization in Quebec that strives "to prevent HIV transmission, to promote community awareness and action, and to enhance the quality of life of people living with HIV/AIDS."

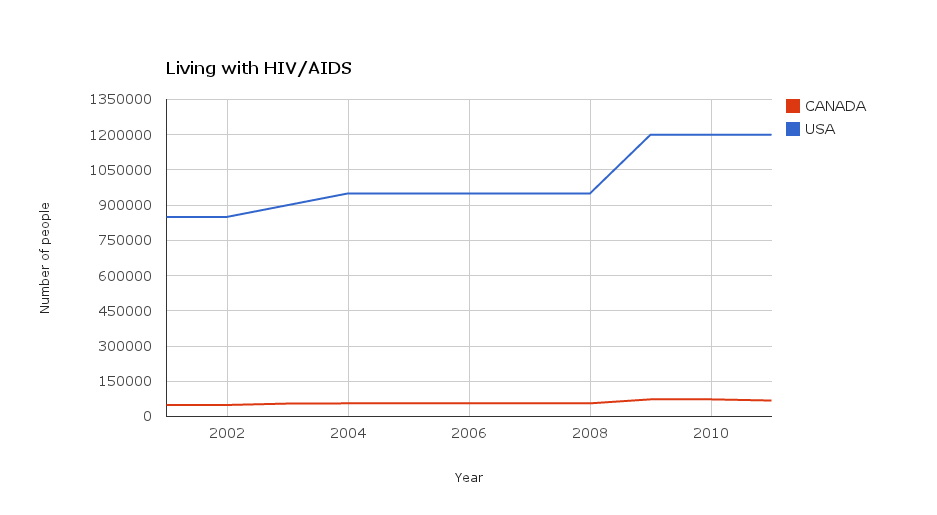

Michael is an activist fighting HIV and the insidious stigma that casts a shadow across those who test positive. In the 25 years since his diagnosis, he has witnessed many changes. Unfortunately, one thing remains the same. People are still getting infected – approximately nine people per day in Canada and 137 people per day in the United States.

Fear of HIV, it seems, has given way to complacency.

"People's perceptions have changed because treatment has improved and it's easier to live with HIV. However, it's not over!" says Michael, his voice rising in anger. "For as long as people believe it's over they're going to have risky behaviours and are going to continue to be diagnosed. And people shouldn't be getting diagnosed because we have all the information, all the tools to rid ourselves of HIV. But people just don't think it's a big deal anymore, so they don't protect themselves."

Michael's frustration is born out of a profound desire to see the end of HIV/AIDS. After a quarter of a century battling every aspect of the virus, he's tired. He doesn't want to witness another generation succumb.

"There is this misconception that HIV is this manageable disease. And so people don't necessarily spend a lot of time thinking about it...until they're infected...or until they know someone that's infected and then all of a sudden their life changes."

Chapter 2: The Diagnosis

Michael's life changed in an anonymous testing clinic in Manchester, New Hampshire. For years he had passively avoided being screened. When HIV tests became available in the mid-80s, Michael was busy travelling the world working for a technology company.

"It was a beautiful, exciting life," he says with a smile.

Afraid of what a positive result would mean for his freedom and his career, he chose to remain ignorant of his status. It's an all too familiar refrain in the world of HIV and one that today Michael works hard to change. He knows early detection is key for successful treatment, but convincing people to test is difficult.

It was difficult for him.

As a young, sexually active gay man in the 80s, Michael knew his risk of infection was high. But it wasn't until 1990, when he came home and unpacked for the last time, that he felt ready to handle a diagnosis.

MICHAEL

That diagnosis would shatter his carefree existence.

To make matters worse, the sympathetic nurse – who delivered Michael's positive test result – delivered an extra piece of unsolicited advice. She told him to "go home and not tell anyone." That if he wanted to access services at the New Hampshire clinic, he should use the back alley door because "it was too dangerous to come in the front."

"I thought that was very strange," Michael says. "Because although it was very early [in the AIDS crisis], I had thought things had advanced enough that I didn't need to hide in the way that she thought I needed to hide."

Michael left the clinic feeling depressed and disillusioned. Five years to live. Grief took over and the darkness closed in. Despite not wanting to hide, Michael found himself retreating from the world. He wouldn't emerge for six months.

Today, most HIV clinics in the US and Canada provide pre-test and post-test counselling to help navigate this difficult process. Medical professionals don't want people to feel abandoned by the system as studies show a patient's knowledge and acceptance of HIV greatly improves adherence to medication. If on-site counselling is not available, clinics will usually provide referrals to organizations such as AIDS Community Care Montreal, where workers like Jessica Dolan help people face their diagnosis in a safe setting.

As the intake intervenant, Jessica is often the first person someone will talk to about a positive test result and what that means. When Jessica speaks, it is obvious why she excels in this trusted position. Her calm and compassionate demeanour has a soothing emotional effect. She is a skilled listener.

JESSICA DOLAN, ACCM

Counselling, group sessions and compassionate listeners are important pieces of a puzzle that help people living with HIV construct a new image of life. HIV is no longer an immediate death sentence. For most, it is a chronic illness. As such, learning how to live, learning how to dream again is paramount.

"With HIV, certainly when people are newly diagnosed today, the reality is that life expectancy is much longer," says Michael – who will soon celebrate his 56th birthday. "But people still lose a connection to their dreams. They lose a connection to their life. And that's one of the reasons why it's so important to do this work because what happens emotionally to people separates them from their lives and they no longer know how to move forward. It shouldn't be like that, not after all these years."

Chapter 3: Stigma

"We are still suffocated and stuck with this stigma associated with HIV."

In 1990, Michael was alone. Yes, he had wonderful friends, friends who were determined to help any way they could...but they were friends who knew nothing about HIV. And after the clinic nurse's disconcerting behaviour, Michael had lost confidence that New Hampshire's health care system could provide the state-of-the-art treatment he needed. It was time to make a change. It was time to go to Boston.

This decision – and a chance encounter in a bar – would save Michael's life.

"I met this man at a bar and during our exchange he told me that he was HIV positive. People just didn't do that back then. And I was curious as to how he felt so sure of himself, how he felt safe enough to share that with me. So I got to know this guy and he introduced me to this organization called Northern Lights Alternatives. It used to do empowerment workshops (it no longer exists), a three-day empowerment workshop to help people dealing with AIDS and HIV to have a better sense of what it was like. To come to some sort of acceptance."

Looking for acceptance, Michael signed up.

MICHAEL

So began the difficult inward journey of therapy. Michael uses a door metaphor to explain the healing process. "The image that I have is you're lead to a door and you're shown a handle...and you're helped to that place and then it's up to you to actually turn the handle and go through the door."

Michael chose to turn the handle.

He chose to confront the pain of his homophobia and the deep self-loathing that whispered things like: you deserve HIV. Of course, no one deserves HIV. Just like no one deserves cancer. But for Michael who was raised in a staunchly conservative, Irish Catholic family, it was difficult. His inner voice was trained to shout that homosexuality was a sin...and by extension, that HIV was his punishment.

The most insidious thing about stigma is how easily one can internalize it.

"I would say the stigma around HIV is the main reason why there is no cure for HIV," Michael says. "That's a pretty heavy duty statement to make. But I've been living with HIV since 1990 and I've witnessed how our society, how modern society views HIV. And it's the stigma associated with it that keeps it alive and transmittable because nobody wants to talk about it. We should be done with this, it shouldn't be that big of a deal."

HIV is a 21st century paradox. People no longer fear death from the virus and so are complacent about protecting themselves, and yet the feeling of being shunned if you test positive is still prevalent. It seems removing the "stain" of HIV is almost more difficult than fighting the illness itself.

Then there are the myths. Myths Michael has spent decades trying to combat – such as if you test positive it's because you're promiscuous or it's because you're a drug user or it's because you are somehow morally corrupt.

"For some reason, we equate who we are as people with this disease," Michael says, getting angry again. "And that's why it's such an invasive disease from a social perspective...because you're marginalized, you're judged, you're flawed because you have HIV. HIV is a virus!"

Linda Farha also blames social stigma for barriers to HIV treatment and prevention. In 1993, Linda's brother Ron died due to complications from AIDS. The pain of that loss is not something her family wants others to experience. It's why they have worked so hard to keep Ron's legacy – the Farha Foundation – alive.

Ron started the charitable foundation in 1992 because "he wanted to make a difference in this world." Twenty-one years and over $9.3 million later, he has.

Yet, it is still not enough. Stigma undermines everything.

LINDA FARHA, FARHA FOUNDATION

Chapter 4: Family

Who to tell is one of the biggest dilemmas for those living with HIV. In 1990, Michael chose to simply tell everyone. Empowered, emboldened and angry after his transformative workshop experience, he stormed into his parent's house and threw his HIV status at them like a weapon. At the time he wanted to hurt them for their beliefs. Beliefs that had damaged him. It's not a moment he's proud of.

Today, life is different. Quieter and more reflective, Michael enjoys a wonderful relationship with his family, although they do avoid talking politics or religion.

"In the very beginning I equated love with acceptance, which was stupid because love and acceptance are not the same thing. I thought because my parents love me that they would accept me and accept my sexuality. But it goes against what they believe morally. So when I stopped fighting it became a lot better. I wanted them to be something that they were not, just like they wanted me to be something that I was not...and I said I'm no longer going to do this."

After facing his parents, Michael decided it was time to face the world. He wanted people to understand that HIV could touch anyone. So, he invited 300 hundred people to a lavish cocktail party fundraiser, got up in the middle of the room and said: "In April of this year I tested positive for HIV infection."

MICHAEL

The bold move had unexpected consequences.

"What ended up happening was people started coming and connecting with me and opening up about the unbelievably hideous things in their lives. And I was like, 'Oh my God, I can't take it anymore, please stop sharing! I'm having a hard enough time dealing with HIV!'" Michael laughs. "But what it really spoke to was being able to be honest and out there and what effect that had on the people around me...and how they came out to love and support me."

For Michael, it was all part of a healing process. One that was moving towards acceptance. And when he was ready to date again, he continued on this journey, telling people immediately about his HIV positive status.

"What I did back then was I chose to be transparent about my HIV status. And when I was rejected, I just went to the next person. And quite honestly, I think it's a problem in most relationships, you know. Why do we want to be with people who don't want to be with us? That's crazy."

MICHAEL

In the end, Michael's blunt dating strategy worked. He is now married.

Chapter 5: Medication

In 1990, the Northern Lights Alternative workshop gave Michael the power to view life from a different angle. In 1996, the new triple drug combination gave him the opportunity to envision a future.

Lifesaving antiretroviral medication had arrived.

For years Michael had been preparing to die and helping others with AIDS make that final transition. Of course, Michael wasn't actually sick. The HIV virus had not progressed for him and with these new miracle drugs he suddenly realized...he wasn't going anywhere. With that realization came a moment of panic. How was he going to finance his future?

Michael had left his high-paying technology career to focus on HIV/AIDS work, believing life would end before the money ran out. For two years, his only job was going "house to house to house helping people die."

MICHAEL

Unfortunately, the miracle drugs that gave Michael hope could not save those whose immune systems were already destroyed. And in 1996 – in the space of two weeks – Michael watched 20 people he loved and cared about slip away. He equates it to being in a war...that "rapid fire of losing people." The grief was unbearable. Michael drank, hoping to forget. It didn't work.

"I needed to step away, so I stepped away from HIV work for a couple of years because I couldn't process the grief. I was never trained for it. I had a business background and a technology background. And I said, 'okay I just need a break. I need to start thinking about myself and taking care of myself and what that's going to mean for the next few years.' And I took a break."

Michael later returned to HIV service work, fell in love with his Canadian husband and moved to Quebec in 2002. He considers himself lucky. Not only was he allowed to immigrate, but his HIV medications continue to work. Not everyone responds to treatment.

With advancements in medicine talk circulates of a vaccine and other types of wonder drugs that will prevent HIV transmission. Promising research and new trials are under way. However, while Michael and Linda Farha would love nothing more than to see a cure for HIV/AIDS, they want people to understand that there's already a way to prevent it.

Know your HIV status and use condoms.

HIV/AIDS Quick Facts - World Health Organization

HIV TRANSMISSION THROUGH:

1. Unprotected sexual intercourse or oral sex with an infected person.

2. Transfusion of contaminated blood.

3. The sharing of contaminated needles, syringes or other sharp instruments.

4. The transmission between a mother and her baby during pregnancy, childbirth, and breastfeeding.

Chapter 6: Future

At age 30, Michael was told to plan his death. Now middle-aged, he needs to plan his retirement. Reflecting on the last 25 years of living with HIV, Michael credits medical advancements, luck and a series of healthy choices for keeping him alive.

"What really made a difference for me is I stopped blaming myself early on and I started working on myself as a whole person. I went to therapy. I started taking the drugs. I started watching what I ate. I reached out to support groups. I found friends. I found services. I spent time healing my life. Maybe that's why I'm doing well. No, no it's not maybe, it's why I'm doing well."

Michael's finances, however, aren't doing so well. Like other long-term survivors Michael's situation is precarious. He didn't plan for the future because he was told in no uncertain terms that he had no future.

It's a bittersweet reality.

Studies show a majority of those who tested positive in the 80s and 90s now live at or around poverty level after giving up successful careers and cashing in pension plans to focus on HIV. They simply never expected to see old age.

MICHAEL